Queuing Theory & Kanban

Kanban centers on process visualization and limiting the number of items worked on at one time, but at its foundation is an alignment with mathematical principles of work accumulation, flow, and stalling, with queuing theory taking center stage.

Pulling work without an awareness of arrival patterns, task types, or work stage capacity rids the Kanban board of its guiding properties. Using the board for making statistically-informed decisions about what work to pull and when reflects the true behavior of the system, letting you control and improve it.

What’s queuing theory?

Queuing theory is an analysis of waiting lines, aimed at predicting the waiting times - the length of the queue. It was developed in the early 1900s for telecommunications, and later embraced in traffic and industrial engineering, computing, software development, project management, and customer service.

Queuing theory offers valuable insights for any structure that manages concurrent, competing tasks, e.g., a customer support ticketing system.

The most common types of queues servicing orders are priority values, FIFO - first in, first out, LIFO - last in, first out, processor sharing - servicing all requests at once, along with SJF and LJF - shortest, or longest job first. Kanban-based workflows most commonly rely on priorities or FIFO:

Queuing theory, Little’s law, and Kanban

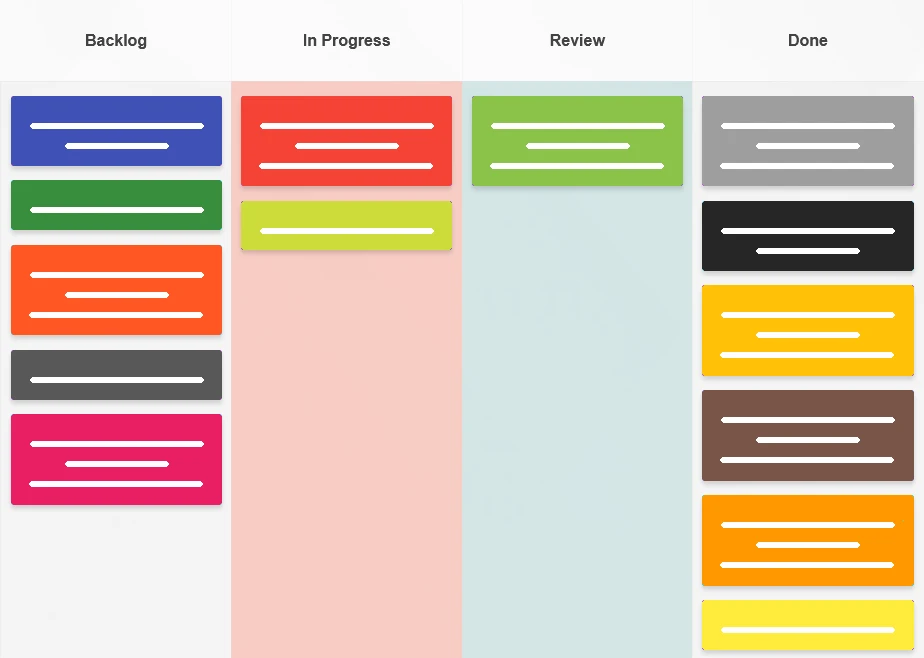

Queuing theory analyzes how units move through a system, focusing on the time each unit spends waiting for an open service/processing opportunity. In Kanban, the units are task cards, and the service opportunities are the available capacity slots in each workflow column.

The dynamics of queuing theory are easy to recognize on the board: a column piling work shows that service rates don’t keep up with task arrival rates, whereas a consistently empty column signals unused capacity, or upstream deficit. Such patterns inevitably present because the math behind queues stays unchanged regardless of industry, team, or workflow size.

In a Kanban system, processing work-in-progress close to full capacity drastically increases waiting times, as even small fluctuations of intake can’t be absorbed, a phenomenon explained by queuing theory. Variability in arrival rates, service time/difficulty, skills, or dependencies shapes queues and cycle times, and ignoring it may lead teams to optimize the wrong areas of action.

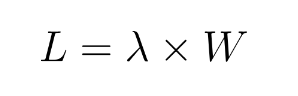

Work-in-progress limits, a hallmark of Kanban, originate from queuing theory and Little’s law, which calculates the average number of tasks in a system (L) through multiplying the average arrival rate (λ {lambda}) by the average time an item spends in the system (W).

WIP limits and dynamic flow in Kanban

Work-in-progress limits are a highly effective mechanism of flow control, and understanding both static and dynamic limits through queuing theory can change a Kanban board from a reactive task list into a predictive, yet flexible system.

1. Static WIP limits

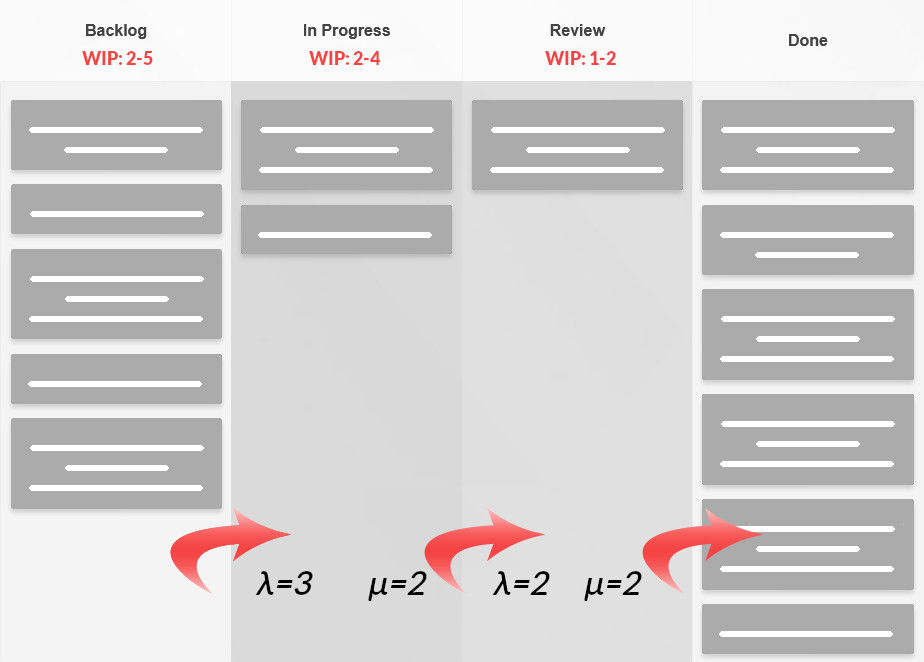

The columns of a Kanban board represent consecutive service steps. Tasks arrive at a rate symbolized by λ - the arrival rate, and are processed at a service rate marked by μ (mu). When the arrival rate exceeds the service rate, a queue forms. Uncontrolled queues cause unpredictable delays, especially when arrival rates spike; meanwhile, a correctly chosen WIP limit binds the system, preventing work accumulation and sustaining set cycle times.

Propped by Little’s law, a WIP limit can be calculated as:

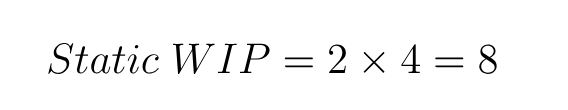

Example

If a work stage completes two tasks a day (throughput), and items remain in it for a total of four days (cycle time), then to prevent overload and sustain an unimpeded flow, the stage limit should be eight items.

2. Dynamic WIP limits

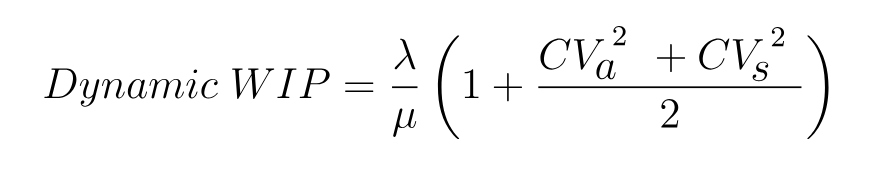

Static, volume-based limits do not adapt to fluctuations in arrival patterns, service variability, or changes in task complexity. To align permitted work with real-time system capacity, a team can enforce dynamic WIP limits, derived from queuing theory.

A process step’s average waiting time and queue length depend on:

- λ: Arrival rate

- μ: Service rate

- CVa: Coefficient of arrivals variation

- CVs: Coefficient of service times variation

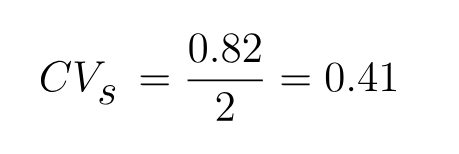

Calculating variation coefficient

To calculate the coefficients of variation, divide the standard deviation by the mean.

For instance, given service times [2, 3, 1, 2 h], with a mean of 2 h and a standard deviation of 0.82, the resulting CVs is 0.41.

The recommended adaptive WIP limit calculation (a Kingman-formula-derived simplification) is:

The formula implies that as variability rises, the WIP limit should be increased to provide additional buffer capacity. Conversely, when variability is low, the limit can be reduced to maximize throughput and minimize waiting times.

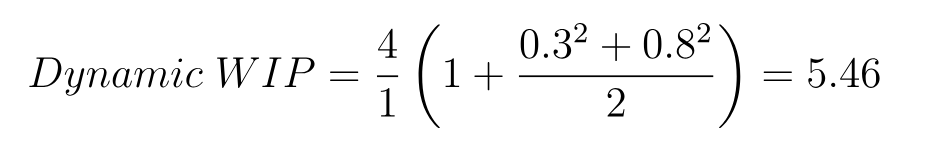

Example: A marketing team’s Copywriting column is characterized by:

- λ = 4 new items arriving each day

- μ = 1 item processed a day

- CVs = 0.8

- CVa = 0.3

Using a dynamic WIP limit of 5 or 6 items, as opposed to a static limit of 4, should allow the system to absorb variability without causing long delays.

Strategic benefits of dynamic work-in-progress limits:

- Flow stability: Queue sizes adjust to current system capacity, preventing unexpected delays.

- Cycle time predictability: Little’s law relationships hold more consistently.

- Capacity awareness: The changing limits act as an early warning of bottlenecks or under-utilization.

- Data-based decision-making: Dynamic limits mean the team’s workload adjusts due to measurable parameters, not arbitrary judgment.

- Scalability: Dynamic WIP limiting applies to a single team flow, cross-functional groups, and portfolio-level Kanban systems.

The spreading bottleneck

A Kanban board naturally visualizes queues: each column corresponds to a service step, each step has a service rate which interacts with both the preceding and following columns. Bottlenecks form at the stages where working times are the slowest or highly unpredictable. However, a bottleneck can easily shift or spread - a team may speed up a slow stage, failing to notice that it reduces variability absorption downstream, causing its service rates to oscillate.

Queuing theory helps teams realize that the goal is not to maximize the speed of every stage, but to balance the flow, preventing all stages from overloading. A column of moderate utilization but minimum variability can stabilize the surrounding stages.

Blocked tasks in queues

Tasks that cannot be moved forward uniquely disrupt a queue, temporarily decreasing the effective service capacity of a column. When several frozen items consume space in the column without contributing to throughput, queues in the preceding stages grow. Queuing theory treats blocked items as service availability interruptions, just as machine downtime in a manufacturing system.

Therefore, the need to analyze blocker patterns is a matter of maintaining system reliability. Recurring blockers are an indication of systemic obstacles that deplete capacity, regardless of staffing level.

Classes of service

Introducing classes of service - e.g., standard, date-driven, ambiguous, and urgent - acknowledges the variability of arrival patterns and requirements. An urgent task entering the system overtakes standard work, distorting cycle time assumptions. From a queuing perspective, urgent tasks represent high-priority “customers” (requests) waiting in a high-priority queue. Giving priority to certain tasks shortens their waiting time, but it does so at the expense of other work, usually causing a cascade of delay throughout the system.

It’s crucial to make these effects clear to the team, as otherwise, they may assume that placing urgency on a task is a harmless exception. Queuing theory reveals the structural cost of making exceptions, encouraging teams to regulate their application.

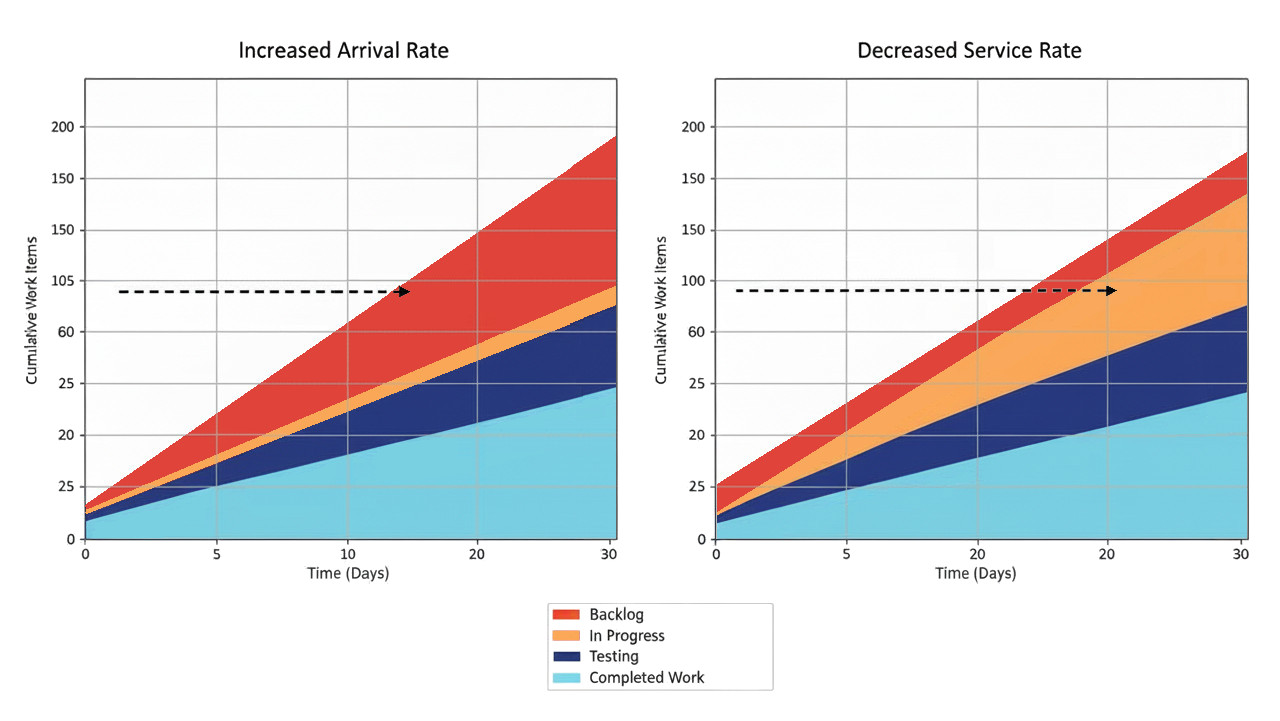

Queuing theory & forecasting

Task arrival rates, completion rates, cycle times, and queue sizes are the raw data required to model system behavior. While many teams find simple averages helpful, a deeper insight can be gleaned from the shape of distributions. For instance, a flow with a broad cycle time distribution (20 days as the top value) behaves differently from a flow with a narrow distribution (8 days as the top value) - despite their averages being similar.

Workflows rooted in queuing theory help analyze and simulate these differences, showing how a system responds to pressure, varying arrival patterns, changing WIP constraints, or the introduction of new classes of service.

Simulating the effects does not require any complex software, as throughput data and a cumulative flow diagram, in particular, can signal whether the system is stable or not.

Did you know?

To simplify applying queuing-theory practices to your workflow, Kanban Tool® provides built-in, automatic WIP limits, cumulative flow diagrams, and clear visual cues for bottlenecks, blocks and classes of tasks. Try the boards today to help your team maintain flow stability with far less manual oversight.

Queuing at scale

Queuing theory can also impact organizational, portfolio-level Kanbans. If multiple work-streams fuel shared process stages, the stages become multi-class queues competing for resources. So when portfolio arrival rates increase without an equivalent extension of service capacity, delays propagate backward, through the entire network of Kanban boards.

In this case, queuing theory proves to leaders that creating more initiatives won’t increase output, but merely increase congestion. On that basis, portfolio-level Kanban can regulate the start of new initiatives, synchronizing upstream readiness with downstream capacity.

When a team understands how queues behave, it can diagnose issues, measure performance, interpret patterns, and improve its Kanban system in real-time. This turns the process from reacting to symptoms into deliberately designing conditions that produce stable flow.

Further reading

- Queueing Systems, Volume I (BOOK)

- Lean Software Development: An Agile Toolkit: An Agile Toolkit (BOOK)

- The Art of Lean Software Development: A Practical and Incremental Approach (BOOK)

- Kanban: How to Visualize Work and Maximize Efficiency and Output with Kanban, Lean Thinking, Scrum, and Agile (Lean Guides with Scrum, Sprint, Kanban, DSDM, XP & Crystal Book 8)