History of Kanban

Kanban has come a long way to become an essential part of the lean management methodology it is today. It’s worth taking a glimpse at Kanban’s rich history, starting during the Edo period in Japan.

1600’s: The roots of Kanban

In 1603, after 14th-century’s devastating near-constant military conflicts and social upheaval have finally ended, Japan entered a period of stability and economic growth. As the country’s economy flourished, the streets of Japanese towns became crowded with shops and local businesses fighting for customer awareness and attention. It’s on these streets where the term “Kanban” was born.

Why is it called Kanban?

The Kanban name comes from two Japanese words, “Kan” 看 meaning sign, and “Ban” 板 meaning a board. As the streets became more crowded, shop owners started to make custom shop signs - “KanBans” - to draw passersby’s attention and tell them about the kind of services rendered by each shop. Soon after, Kanban sign designers started to compete by artistically crafting their signboards, to make them stand out from other Kanbans on the street - a practice very much still alive today with modern neon designs. Looking at the rich collection from those times, you will see a fisherman’s Kanban looking like a fish, or an artistically styled wooden pipe Kanban, made for a pipe shop.

All these Kanban signs had one thing in common - just like modern Kanban cards, they were able to communicate their content clearly and concisely.

1940’s: Toyota’s Lean manufacturing Kanban

To produce only what is needed, when it is needed and in the amount needed. Taiichi Ōno

“Everything keeps going right: Toyota” was a slogan for Toyota years ago, and it stuck. But this was not always so.

In the 1940s Toyota was far from the industry giant we know today. After the second world war, the Japanese car industry was in stagnation. Toyota was firmly making a loss, could not compete at all with any of the American car manufacturers, and was in such poor shape that they were not able to hire any new staff. But Toyota’s CEO, Kiichiro Toyoda, was on a mission to change that. He did realize that the tenfold difference in productivity between USA car manufacturers and Toyota cannot be explained solely by the lack of equipment - the matter was more complex than this. Yet he set the company on a quest to equalize productivity with American automotive manufacturers in three years. Even though such an ambitious goal was hardly attainable, it has set the company on a course grounded in innovation and optimization of work organization for years to come.

This change in company culture has cleared the path for Taiichi Ōno, a young industrial engineer who has just been transferred to Toyota Motor Company in 1943.

Taiichi Ōno, source: wikimedia.org

Taiichi Ōno, source: wikimedia.org

Taiichi Ōno had a strict-but-fair character and quickly rose through the ranks at Toyota. In 1949 he became the machine shop manager, which allowed him to start experimenting with new tools and principles of work organization. In 1954 he was promoted to a director position.

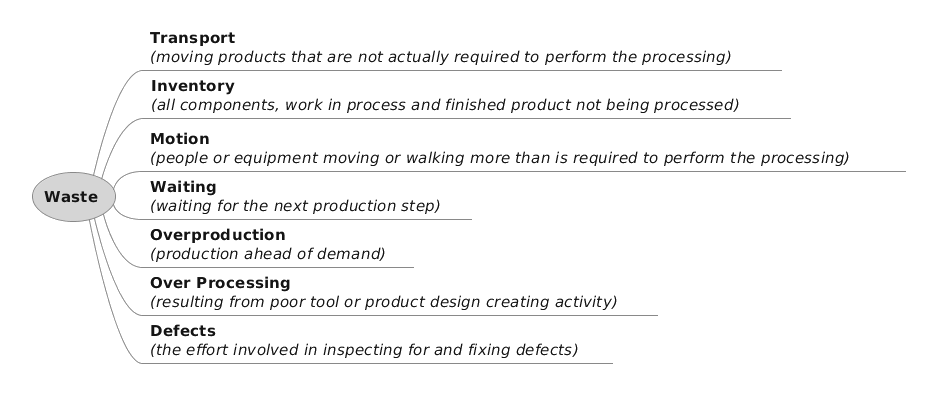

Ōno identified and categorized seven kinds of waste (jap. Muda), which lead to a decrease in system throughput and performance.

Seven kinds of waste (Muda)

Seven kinds of waste (Muda)

Overproduction was a waste, as customer demands may change over time, but so was keeping a large inventory of raw materials. The only solution to this apparent paradox was to produce what is needed and only when it’s needed. It required keeping the stocks to a minimum while ensuring a smooth and high flow of work through the whole process. But this approach had its problems. How to signal that a new product is required? How to propagate this signal back to the production line and eventually to the raw materials suppliers?

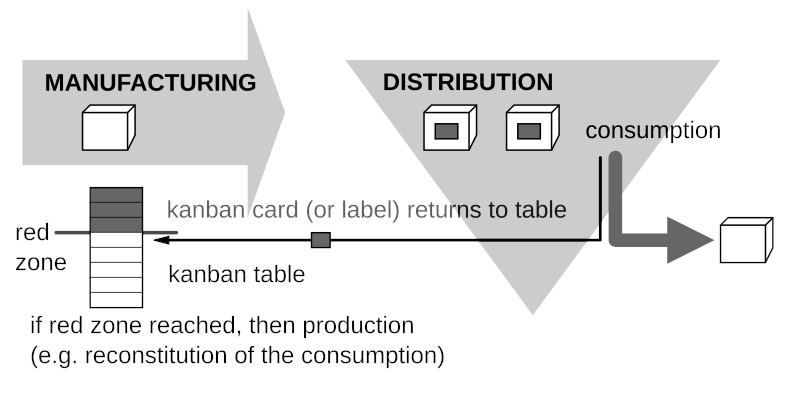

With help came retail supermarkets. Ōno visited the United States in 1956, and he was impressed by how supermarket chains Piggly Wiggly was able to keep the shelves stocked with just the right amount of each product. After coming back to Japan, he began to use paper cards for signaling and tracking demand in his factory, and named the new system “Kanban”.

Kanban cards were attached to every finished product, and once it was sold, the cards would move back to the production line. Team members could only work on the new item as the card signaling a demand for it moved back to them, and only once the number of pending Kanban cards reached a defined threshold. Every material used during production also had its own Kanban card attached, so that the demand signal would ultimately flow down through the whole production chain, ending on external suppliers.

Manufacturing Kanban, source: wikimedia.org

Manufacturing Kanban, source: wikimedia.org

Such a system reduced stockpiles, improved throughput, and provided high visibility into the process. Its usage has quickly spread through the entire Machining Division. In 1963 a plan was developed to propagate it further to the whole company, and shortly it was adopted in nearly all processes at Toyota.

The power of the Kanban application was such, that Toyota went from operating at a loss to the global competitor it is today. Taiichi Ōno rose through all of the senior ranks of the company and became an executive vice president in 1975. His work gave rise not only to the new meaning of “Kanban” but also laid the foundation for modern management techniques, known as Toyota Production System.

2003-2008: Kanban for the software industry

As the Toyota Production System was gaining popularity and word about it was spreading, project managers from different kinds of industries tried to apply its core teachings to their work.

The most significant breakthrough came from the Software Industry.

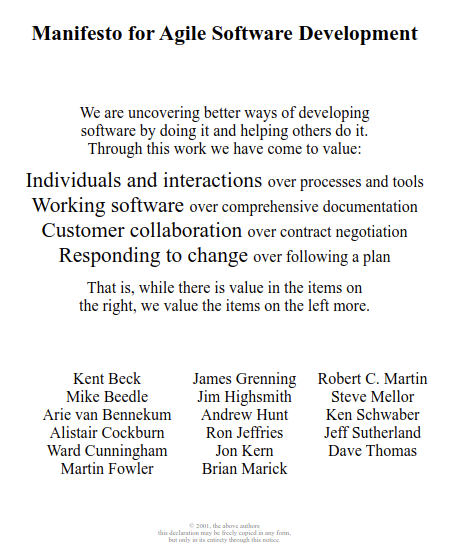

Around that time, project management in Software has already been gradually shifting from cumbersome and inefficient processes like the CMMI toward a more light, “agile” approach, which got formalized under the Agile Manifesto, published in 2001.

Manifesto for Agile Software Development,

Manifesto for Agile Software Development,

The Agile Manifesto and its underlying principles provided general advice like “Welcome changing requirements” or “Deliver working software frequently”, but did not specify how this should be achieved. Hence, several work management systems quickly evolved to fill this void, embracing the Manifesto and becoming the core of Agile software development at that time. Most notable of them were Scrum, eXtreme Programming and, a little later, Lean Software Development.

Elements of Scrum, Lean Software Development, and Agile Management had a significant impact on what was about to become the Kanban method.

-

Scrum

Many scrum teams used pinboards with user story cards, as information radiators. This usually worked like this - during the sprint planning, each user story, or a feature to be implemented, was written on a separate physical card. Together, these cards formed a sprint backlog and were placed on a big board somewhere in the office, accessible to all team members. Each team member could walk up to the board, take a look at the stories and pick one, which they wanted to implement next. They’d then take such a card to their desk, and once the work was done, the card was struck-out and returned to the board. This simple system was ingenious. It provided high visibility into progress, allowed for synchronization of work between multiple programmers, and improved the flow of work since each programmer could pick the type of work they felt best at. -

Lean Software Development

In 2003, Mary and Tom Poppendieck published a now-classic book on software development, “Lean Software Development: An Agile Toolkit”. The book translated the lean manufacturing principles out of Toyota Production System to the software development and knowledge work domain. It focused on eliminating waste, mapping the value stream, and on pull systems. It was followed in 2007 by another book by the same authors, “Implementing Lean Software Development: From Concept to Cash”, which further explored using queuing theory to reduce software delivery times, and Kanban boards as an element of the Visual Workspace. Also, in 2005 Jim Sutton and Peter Middleton published “Lean Software Strategies” which identified the five principles of lean production - defining value, mapping the value stream, implementing flow, maintaining a pull process, looking for improvement opportunities - and applied them to Software Development. -

Agile Management

Apart from Scrum and Lean Software Development, other concepts of how teams could become more agile were also explored. In 2004 David Anderson published the book “Agile Management for Software Engineering: Applying the Theory of Constraints for Business Results”, which covered concepts such as flow, bottleneck, visual control and cumulative flow diagram, all of which he later incorporated into the Kanban method.

At that time, some software development teams, already using Scrum boards, embraced these new techniques and re-organized their boards by introducing columns representing the distinct stages of work, thus giving rise to Kanban boards.

Kanban boards, combined with other Lean Software Development and Agile Management methods, such as Pull Scheduling, Limiting Work to Capacity, and Measuring Flow, gave rise to Kanban-style software development.

This early Kanban gained acceptance as a system of its own, as it helped with the things that Scrum was not particularly good at shortening the cycle time from customer request to delivery and ensuring a constant flow of work.

In classic Scrum methodology, after a sprint planning session, the Spring backlog gets frozen, no changes to it can be made. That state lasts usually from 7 to 30 days, as the team progresses through the backlog, and at times it can be frustrating both to developers and final customers. What to do if there is an emergency, and a specific feature needs to be implemented quickly? What to do with all the bugs discovered in the live product - do final customers need to wait over a month to get them fixed? And finally, how to handle processes, that are more dynamic by their nature, like website marketing or server administration?

Kanban method, with its Kanban boards and focus on flow, became an answer to this, providing a highly structured, visible, and flexible way of managing work.

As the adoption of Kanban-style software development slowly grew, a few pioneers have helped to spread the knowledge about it, and shape its ultimate future.

-

Mary and Tom Poppendieck

Marry and Tom Poppendieck were among the first people who embraced and spread the knowledge about Toyota Production System methods applied to software development and knowledge work. They spoke at numerous conferences and published books covering topics such as Value Stream Mapping, Queuing Theory, and Visual Workspace that lay at the foundation of Kanban. -

Microsoft

Probably the first attempts to introduce the principles of Kanban into software development methods were made in Microsoft. To increase productivity, software development teams have started to add elements of Scrum and Kanban as an extension to the existing “Feature Crew” model and “Bug Jail” method. This has resulted in the first successful Scrumban project in 2004. -

David Anderson, Dominica DeGrandis, Corey Ladas, and Daniel Vacanti

In 2005 David Anderson was working on implementing the drum-buffer-rope system described in his book, at the XIT Sustained Engineering team in Microsoft. In 2007 he left Microsoft and moved to Corbis, with a mission to change Corbis engineering and improve productivity. There, together with Dominica DeGrandis, he introduced a Kanban system for change requests processing. It has freed the team from constraints of time-boxed iterations, allowed to reduce work in progress, and balance capacity against demand. In the spring of 2007, Corey Ladas has joined Corbis to launch the second kanban project, which was a Scrumban process for product development rather than just maintenance. In summer 2007, Daniel Vacanti joined Corbis and, together with Corey, was working on a third big Kanban project aimed to demonstrate Kanban at Scale. It introduced the concept of swimlanes to keep related work items bound together. In August, David has run an open space at the Agile 2007 conference, speaking about the successful implementation of Kanban at Corbis, which sparked the initial interest in Kanban boards and the Kanban method. -

Karl Scotland

Karl first heard about the Kanban method at the Agile 2007 conference. In September 2007, as a Yahoo! Engineering Program Manager, Karl introduced Kanban to his team, as a solution to the Sprint length problem in Scrum methodology. This implementation was highly successful, and Karl became one of the first and most prominent proponents of the Kanban method.

These initial successes have driven wider attention to Kanban.

In 2008 a Yahoo! group kanbandev was formed to provide a ground to discuss and learn more about the use of virtual Kanban systems in software development, and it shortly grew to over 1000 members. Aaron Sanders, Alan Shalloway, Alisson Vale, Allan Kelly, Chris Shinkle, Corey Ladas, David Joyce, David Laribee, Derick Bailey, Eric Landes, Jeff Patton, Joe Arnold, Karl Scotland, Linda Cook, Matt Wynne, Mattias Skarin, and Rob Hathaway were prominent pioneers of the Kanban method.

2009: Kanban gains momentum

The truly golden year for Kanban was 2009.

In January 2009, drawing from his experience at Corbis, Corey Ladas published “Scrumban: Essays on Kanban Systems for Lean Software Development”, which was an attempt to mix Scrum, Lean and Kanban.

Around April 2009, Henrik Kniberg published “Kanban vs. Scrum – a practical guide”. The article covered the basic principles of Kanban in an easy to understand way. For many people, this was the place they first learned about the Kanban method.

In May, the 2009 Lean Kanban conference, organized by David Anderson, took place at the Mandarin Oriental Hotel in Miami. It featured the latest developments in the application of Lean Thinking to software development.

Following the conference, an informal Limited WIP Society was formed, with the mission to unify and spread knowledge about the Kanban method. The society provided a platform for the aggregation of articles on Kanban, which helped to spread awareness of the method further still.

In the summer of 2009, Jim Benson began publishing articles about Personal Kanban, which focused on applying Kanban principles to the organization of personal life, which later became a method of its own.

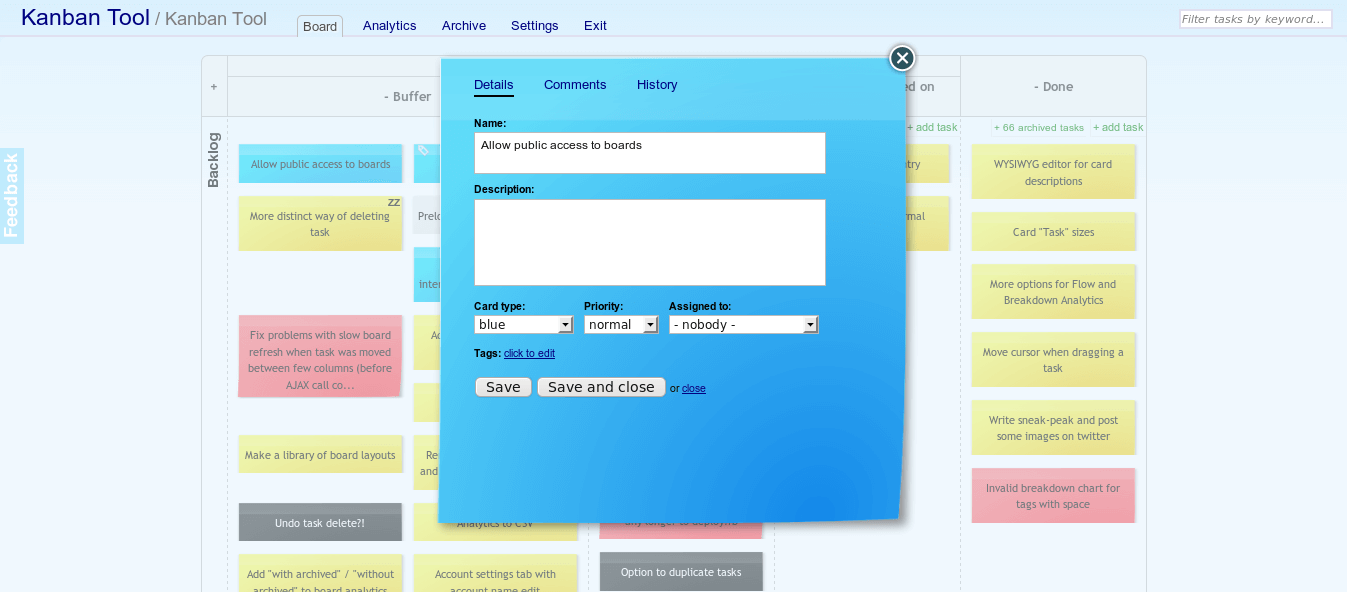

Also in 2009, the first web-based applications to manage projects and business processes with Kanban method have emerged, making ground for wider adoption of Kanban principles outside of the Software Industry: Agile Zen, Kanban Tool and LeanKit Kanban.

An early version of Kanban Tool, source: kanbantool.com

An early version of Kanban Tool, source: kanbantool.com

Did you know?

Kanban Tool® was one of the first web-based management solutions that focused on visual management of business processes and utilized principles of the Kanban method. It has evolved over the years and is still regarded as the top choice in the project management space. Give it a try and empower your team.

Past 2010: Kanban for everyone

As knowledge and usage of Kanban grew, it became apparent that Kanban works well not only in Software Development but basically in any repeatable process. Manufacturing, sales, marketing, recruitment - every kind of process could benefit from Kanban. Even the U.S. military was eager to adopt its principles. While more and more success stories were being told, it started to become clear, that the Kanban method needs to have some underlying principles defined.

In March 2010 Henrik Kniberg and Mattias Skarin published a free mini-book “Kanban and Scrum - Making the Most of Both”, that later got translated into 14 languages.

In April 2010, David Anderson published “Kanban: Successful Evolutionary Change for Your Technology Business”. Even though it focused on technology businesses, it offered some general guidance on the implementation and use of Kanban.

In 2011 Jim Benson and Tonianne DeMaria Barry published “Personal Kanban”, showing that Kanban can also be successfully applied on a personal level.

Numerous other books and online articles about Kanban began to appear, documenting individual experiences with Kanban, and its various applications.

Finally, in 2016 “Essential Kanban Condensed” was published, distilling the application of Kanban into five practices:

- Visualize Workflow

- Limit Work in Progress

- Measure and Manage Flow

- Make process policies explicit

- Use Models to recognize process improvement opportunities.

Unless you have implemented all these routines, you may have a Kanban board, but you’re not benefiting from the complete Kanban system.

To learn more about applying Kanban to your work, read Kanban Fundamentals.

Further reading

Kanban signs:

- Kanban: Traditional Shop Signs of Japan (BOOK)

- Handcrafted Japanese Shop Signs Perfected the Art of Advertising

Toyota Kanban:

- A timeline of Toyota Production System development (PDF)

- Toyota Production System: Beyond Large-Scale Production (BOOK)

Kanban for the software industry: