Kanban, Scrum & Scrumban

The choice of a process framework for a product or service delivery team strongly shapes how it thinks, coordinates, and adapts to change. While Scrum, Kanban, and Scrumban - a hybrid of the two - all have a foundation in Lean and Agile thinking, their guiding concepts diverge significantly in their interpretation of flow, adaptability, and control.

Scrum is prescriptive, defining flow structure, cadence, and team member roles for the purpose of facilitating discipline in the face of uncertainty. Kanban is evolutionary, seeking enhancement by observing and fine-tuning existing workflows, relying on process transparency and continuous flow. And Scrumban exists in between the two - not as a compromise, but as a synthesis - a trick for teams to adopt Scrum’s coordination benefits together with Kanban’s flexibility and throughput optimization.

The three frameworks are often misunderstood or applied superficially, with little regard for their underlying principles. Teams frequently go through the motions of Scrum rituals without reflecting on sprint outcomes, or use Kanban boards merely as task trackers, ignoring WIP-limiting discipline. And Scrumban is often seen as a compromise, while its true purpose is to reintroduce discipline where the structures of Scrum or Kanban alone prove inadequate.

Here, we examine the three frameworks in depth: their origins, mechanics, applications, and weaknesses, to support your deliberate, informed choices.

Scrum: The structured iteration framework

In the 1990s, Scrum emerged as an empirical framework to facilitate concurrent engineering in the software industry. Its goals were to improve the speed of product delivery and to raise responsiveness to changing requirements and market conditions. Scrum divides work into iterations spanning 1-4 weeks. Each sprint - the time-boxed iteration - is a self-contained window in which a team commits to delivering a potentially shippable increment of the product.

Scrum’s team roles, artifacts, and ceremonies

- Product owner - responsible for maximizing product value and curating a prioritized backlog.

- Scrum master - facilitates adherence to Scrum principles and helps resolve bottlenecks.

- Development team - a small, cross-functional group, self-organizing to deliver work items selected by the product owner.

The characteristic artifacts of Scrum are the product backlog, sprint backlog, and increments, providing process transparency and traceability. The ceremonies, working to create cycles of planning, feedback, and improvement, are sprint planning, daily stand-ups, sprint reviews, and sprint retrospectives.

Scrum application and challenges

Scrum thrives in high-uncertainty environments, where product requirements evolve quickly and broadly; the framework delivers just enough structure to bring discipline without limiting adaptability. While Scrum provides rigor, it can become a constraint in projects that lack defined release cycles or consist primarily of ongoing maintenance and operational tasks.

Long-standing difficulties for Scrum teams are role enforcement and velocity metrics. Having to define a single product owner, assign estimated story points to tasks, and calculate process speed often becomes too much of a bureaucratic overhead. Though Scrum philosophy encourages empiricism and adaptation, teams often slip into reducing it to structural ritualism, with ceremonies becoming checklists instead of growth opportunities.

Even with its shortcomings, Scrum continues to serve as a standard in software development for structured teamwork and iterative delivery, done in a clear and teachable fashion.

Kanban: Continuous flow and evolution

Kanban originated at Toyota as a method for managing inventory and was eventually adapted to software and knowledge work by David J. Anderson. As evolutionary, not revolutionary, Kanban lets teams begin with exactly the process they had before, just visualized and gradually improved.

Kanban does not impose specific team roles (though they can emerge), iterations, or ceremonies. Instead, it centers on five general principles:

- Visualize the workflow: make every task’s status visible on a board divided into distinct workflow stages - the columns of the Kanban board.

- Limit work in progress (WIP): cap the number of tasks that can be active in each stage.

- Manage flow: use real-time data from the board to spot bottlenecks and optimize flow.

- Work with explicit policies: the rules guiding when items can move from one stage to another have to be clearly defined.

- Improve continuously: regularly review the process for flaws, and adjust the environment to mitigate them.

Kanban application and challenges

The continuity of a Kanban-based workflow is its core strength. Thanks to WIP limits, new tasks are only pulled from the backlog as capacity becomes available; there are no set time-frames or deliverables. And that is what makes Kanban ideal for operations, support, and ongoing product management, where the focus is on flow stability, as opposed to time-fixed outcomes. Kanban reduces over-commitment and multitasking, exposing inefficiencies as they occur.

Following a Kanban process can feel alien to teams used to traditional project management. Without Scrum-style rituals, teams can initially struggle with cadence and accountability. Kanban’s adaptability can be both its virtue and a problem, as it demands a culture of self-discipline and ongoing analysis to succeed.

Scrum and Kanban similarities and differences

Process transparency, continuous improvement, and flexibility are promoted in both Scrum and Kanban, yet their fundamental assumptions differ.

| Dimension | Scrum | Kanban |

|---|---|---|

| Cadence | Time-boxed sprints (1–4 weeks) | Continuous flow |

| Roles | Defined (Product Owner, Scrum Master, Team) | Undefined; existing roles retained |

| Planning | Mandatory sprint planning | Continuous, demand-driven planning |

| Delivery | At the end of each sprint | As soon as work is complete |

| Work in progress | Indirectly limited by sprint scope | Explicitly limited by WIP caps |

| Change policy | Scope frozen during sprint | Changes allowed at any time |

| Metrics | Velocity, burndown charts | Lead time, cycle time, cumulative flow |

| Suitable for | Teams delivering iterative product increments | Teams focused on continuous operations or service delivery |

The iterative nature of Scrum forms predictable checkpoints for feedback, making it highly suitable for new product development, where cyclical releases and stakeholder alignment are imperative. Meanwhile, Kanban shines where flow efficiency and process optimization matter most, emphasizing visualization and continuous improvement rather than dictating how work is organized.

Scrumban: The practical hybrid

The Scrumban hybrid allows teams to make the best of both worlds, to meet their specific needs. It’s often recommended that mature teams move from Scrum to Kanban, and Scrumban is a good way to complete this transition, though often, teams choose to simply remain in Scrumban. In a way, Scrumban is more aligned with Kanban than with Scrum, in the sense that it’s easier to apply to various applications, given that it’s less restrictive than Scrum.

The term Scrumban was coined by Corey Ladas, the author of “Scrumban: Essays on Kanban Systems for Lean Software Development”.

The origins of Scrumban: Adopting Scrum is hard

Transitioning to Agile is challenging for most teams, often requiring a mind-shift that can be difficult to grasp. Also, due to the popularity of Scrum, many managers think of Scrum alone, when they think of Agile, despite there being numerous other (potentially easier to adopt) frameworks available, i.e. Kanban, XP, DSDM, etc.

Although there are many success stories around teams who have implemented Scrum, if you could speak to those teams, they would likely tell you that achieving success with Scrum has not come easy. For the most successful companies, it often took 12 to 16 weeks to develop a discipline to make Scrum work. It’s common for companies to require serious outside consulting help with this. Businesses often struggle with finding the new required roles of product owner, scrum master, and development team. For many, this is a bit of an HR disaster.

Furthermore, calculating story points and measuring velocity - while not required as part of Scrum, according to the official Scrum guide - has grown to almost be a necessity. Most teams struggle to understand this, with Scrum masters complaining how challenging it is to do it properly. Scrumban makes it possible to avoid all this unnecessary confusion.

Project managers are used to handling ventures that have a definitive start and end date. They are often made up of cross-functional teams that might be together for 12 months or less. Teams like this can work well with Scrumban, through learning communication structures based on some of the Scrum ceremonies, with dedicated planning sessions to discuss project requirements.

Also, for many projects, specifically infrastructure ones, there will not always be a shippable product at the end of each sprint, which is one of the requirements of Scrum. Rather, teams would work continuously and move to production or another iteration when ready. Now, the Scrumban approach embraces an existing system or product lifecycle and simply adds to it the visibility of Kanban with some of the Scrum ceremonies.

What’s more, with Scrumban, project managers don’t have to forcibly find a single product owner to control the backlog. The role of a product owner is critical to Scrum, but in corporations, there are often multiple stakeholders with different kinds of requests, making it impossible for a single person to prioritize stories or issues. Scrumban does not call for standard-sized stories or a single backlog owner, but simply asks teams to ensure that the backlog is in clear view of all.

Scrumban application: From iterations to continuous delivery

Scrumban allows teams to shift from having to keep a set of determined planning times, to planning only when required. New to-do items might be discovered regularly in production. As opposed to Scrum, Scrumban does not force product teams to limit the sprint scope to 1-4 weeks, allowing production to take as long as is needed for the best results. While from a project perspective, this is where it ends, for most companies, this is just the start of the journey. Projects are carried about so that the temporary change initiated by them can continue to operate and realize benefits, and Scrumban is very useful here.

Teams that have been using Scrum, may find it easiest to move towards Scrumban in the latter part of a project - when they transition from product development to maintenance and take on a continuous flow approach.

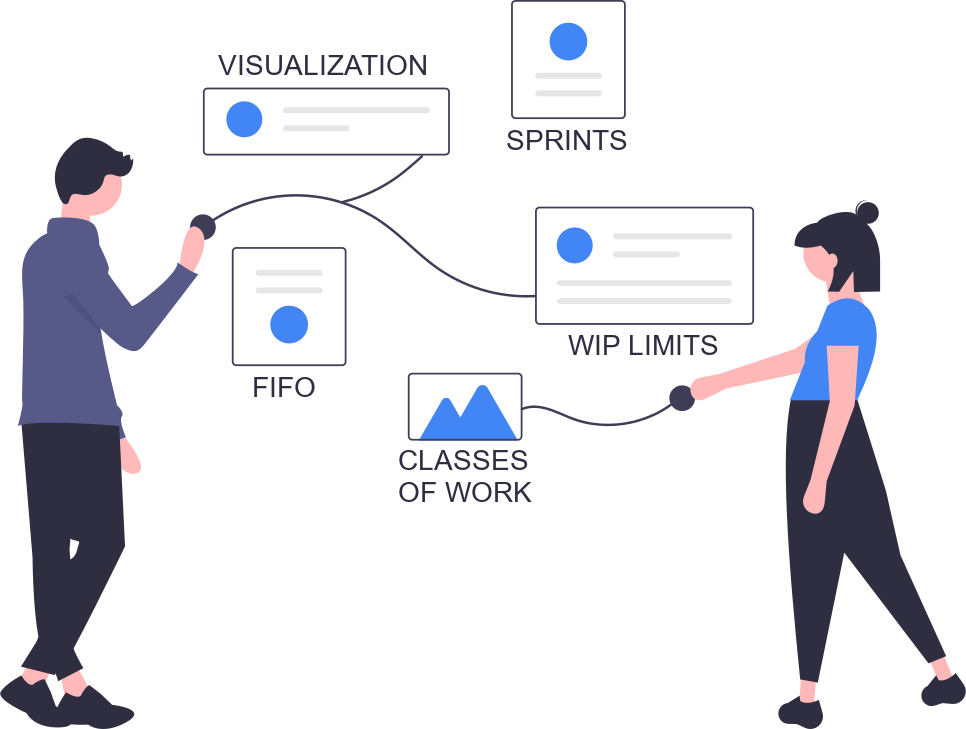

The Scrumban difference

Typically, teams using Scrumban boards will divide the workflow into more stages, than they would on a Kanban board. That is to show a more gradual nature of the process, stemming from the sprint-like approach to project planning. Very often, a Scrumban board still does incorporate a “sprint” stage or a “Stories” types of items. On those boards, it’s possible to track the progress of work related to a specific story or a specific sprint, regardless of the team working continuously.

Also, Scrumban teams are typically freer to prioritize items in columns, than people working with Kanban, which does tend to prescribe sticking to the FIFO rule.

As companies realize they need to move to a more Agile, Lean way of working, Scrumban is an easy way to go, with its removal of any unnecessary clutter from Scrum, that many a company will not need. It allows companies to continue to work in a way that is natural to them, but to - at the same time - implement the best Lean and Agile practices specific for continuous flow environments.

| Characteristics | Scrumban |

|---|---|

| Roles | Not predefined. The team plus needed roles, i.e. a project manager, etc. |

| Meetings or sessions |

Whatever is required to make continuous progress. Often daily stand-ups as a minimum. |

| Demos and retros | As and when needed - aren’t fixed for the end of each sprint. |

| Iterations | Not fixed, working in a continuous flow. |

| Work method | Pull with WIP limits. |

| Burndowns | No, only a Kanban board. |

| Velocity tracking | No, but focus on removing bottlenecks is recommended. |

| Estimation | Items on the board are similarly sized, but not fixed with story points. |

| Backlog | Driven by JIT (Just-in-time), as needed. |

| Scope | Not locked, the board is updated regularly. The workflow is not overloaded but based on JIT and throughput. |

Choosing between Scrum, Kanban, and Scrumban

Scrum is most effective when:

- The product is actively developed, and requirements change rapidly.

- Stakeholders demand formal feedback cycles.

- The team is newly formed, benefiting from structure and explicit roles.

- The company values predictability of delivery and gradual progress.

Kanban excels when:

- Work is ongoing, continuous, and tasks vary in size.

- The team is experienced in collaboration and self-management.

- The goal is process optimization, rather than reaching the end of an iteration.

- Priorities and requirements fluctuate.

Scrumban fits best when:

- The team is transitioning from Scrum to a flow-based model.

- The work doesn’t benefit from fixed iterations.

- The company values visibility and structure, without extensive rigidity.

- It’s necessary to coordinate between multiple concurrent work streams.

Did you know?

Although Kanban Tool® was built with Kanban process flow in mind, it’s up to you to define how your boards operate. Working along with Scrum, Waterfall, Scrumban, or any other pattern is possible. See for yourself - build your board now, exactly how you want to.

Practical advice for common pitfalls

- Scrum: Too much emphasis on story points, team roles, and sprint deadlines can erode team motivation. The team should treat Scrum ceremonies as opportunities for collaborative problem-solving, not compliance.

- Kanban: Without sufficient discipline, Kanban can devolve into chaos. The team should maintain strict WIP limits and work stage policies, committing to continuous process verification.

- Scrumban: The same flexibility that makes it appealing can lead astray if discipline is lacking. The team should still define explicit working agreements and review them cyclically.

Adopting any of these frameworks requires adoption of systems thinking - a team will be more successful through understanding not only what the framework prescribes, but also why. Cultivating work predictability, quality, and responsiveness should be the ultimate goal of adopting an Agile framework.

Final thoughts

Scrum, Kanban, and Scrumban all provide different yet complementary approaches to planning team delivery within Agile and Lean environments. Ultimately, no framework is universally superior: Scrum offers structure, Kanban flexibility, and Scrumban reaches a balance of the two. Success doesn’t lie in religious adherence to chosen method, but in intentionally applying its principles to enhance transparency, increase team empowerment, minimize waste, and facilitate continuous improvement. That’s the shared spirit of Scrum, Kanban, and Scrumban.

Further reading

- Scrumban - Essays on Kanban Systems for Lean Software Development (Modus Cooperandi Lean) (BOOK)

- The Epic Guide to Agile: More Business Value on a Predictable Schedule with Scrum (BOOK)

- An Empirical Study of Scrumban Formation based on the Selection of Scrum and Kanban Practices (research paper)

- Scrumban: An Agile Integration of Scrum and Kanban in Software Engineering (PDF)

- Popular articles about Scrumban in the Kanban Library