What is Muda?

Why does understanding waste in a business process matter?

When looking to increase your process efficiency and reduce costs, the first points of interest might be: what can you cut down on, what can you stop doing or change. To find that out, you first need to be able to tell the difference between which parts of the process are necessary and which aren’t. Also, which actions make the product valuable to the customer and which don’t - but still need doing?

What does muda mean?

Muda is a core concept of waste in the Toyota Production System (TPS), the building block of Lean management. As one of the 3M - together with mura and muri - it serves to identify the non-value-adding activities within a process. The Japanese “muda” word (無駄) translates as uselessness, futility. In Lean management, muda is those changes or actions that do not cause a value-increasing effect on the product, an effect that the customer will be happy to pay for.

Muda, as actions adding no value to the product, takes on two forms:

- Type one muda:

non-value adding actions, which nevertheless have to be performed. The best example of type 1 muda is safety tests and inspections. They don’t improve the product as such but have to take place. - Type two muda:

non-value-adding actions that have no impact on the end product or the integrity of the process delivering it. It’s the kind of waste that needs eliminating.

How to identify process waste that needs removing?

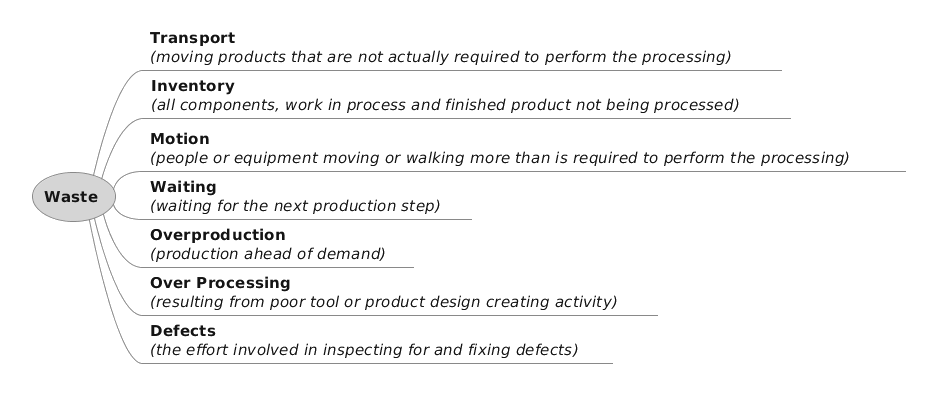

Type two muda was furthermore split into seven categories by the father of Kanban, Taiichi Ōno. Thanks to that, identifying pointless actions becomes even easier for process managers. The seven types of muda lie in transportation, inventory, motion, waiting, overproduction, over-processing, and defects.

Seven kinds of waste (Muda)

Seven kinds of waste (Muda)

Step 1: Transportation

In a manufacturing scenario, materials, half-made-products and final products need to move between work stations, stock areas and the like - it’s necessary. But the more complex an environment, the more room there is for adding extra redundant steps to these travels. And each time a batch of material goes somewhere, there is usually a set of documents following it, requiring signing or looking over at each checkpoint. It’s crucial for the materials to take as few trips between the various process steps within your permises as possible.

The same goes for knowledge work processing. If every time you need a superior’s opinion on your task, you have to pause it, take a trip to their office, explain what you’re having a problem with, wait for the answer, then get back and resume work - you are wasting time on the trip. Imagine typing a quick comment on the task placed on your digital Kanban board and sending it to the boss instead. They’ll reply when they can, having access to the task’s full description, saving you doing any talking. Meanwhile, you can get busy with another item from the queue and get back to the problematic one once you’ve got the answer.

Step 2: Inventory

Waste caused by inventory refers to accumulation of either raw materials or finished products in the facility. Adding too much Work In Progress to either stage of your process will inevitably cause a bottleneck and hurt productivity. And stocking too much of finished goods is also a waste. If you have to pay for storing unordered products, you’re clearly not adhering to the Just-in-time (JIT) production concept. You’ve invested into a product you have no buyer for.

In knowledge work, the inventory waste shows as the exceeding of your Kanban board’s WIP limit. The more tasks you start to work on at once, the more slowly they will get done. It’s much more efficient to stick to the limit and not begin new work until your hands are free from previously opened tasks.

Step 3: Motion

While waste in transport deals with inefficiency caused while the product moves between the process steps, motion waste refers to how items move within a single process stage. For a production facility, this kind of waste may result from the use of not serviced machines, from untrained workers damaging the product or causing unplanned stops, from suboptimal factory layout, unnecessary motion and tool changes.

For non-physical work, motion-related waste within a process stage are usually unnecessary emails, calls, meetings that could all be replaced with a status change on the individual task card.

Step 4: Waiting

In many ways, the waste caused by items waiting to be processed is the easiest to spot but not always equally as easy to remove. Jobs or tasks will be queuing for extended time between process steps when your process either lacks the ideal capacity to pull all tasks at once, or when the started items processing is not going optimally. Bottlenecks form, with consequences visible on all following process stages.

The standard Lean methods to reduce waiting are production levelling, or Heijunka, with applying and adjusting WIP limits. Crucially, consider limiting the designated “waiting” steps - i.e., the “ready for another stage” ones. If you decide how many items can pile up in them before teams from other process stages step in to help, you will likely avoid late deliveries and costly impediments.

Did you know?

Digital Kanban Tool® boards support automatic WIP limit counters in each process stage. With the boards, you’ll get an “at a glance” overview of your production state and will be able to act on solving bottlenecks as soon as they occur. Try them with your team today!

Step 5: Overproduction

As signaled before, a Lean process will only produce what was ordered and can be capitalized. Working round the clock to manufacture endless batches of a product that clients have not yet ordered is a waste of time, resource (capital included) and material. Neither stock nor products filling up your warehouse are assets from an accounting point of view - they will only become such after you sell them.

The worst risk you run by overproducing is not considering that the clients may change their ordering pattern or frequency. To stay agile in how you produce, stick to adjusting production to orders, not looking for outlets of already manufactured goods.

Step 6: Over-processing

The problem with over-processing items usually ties to miscommunication with clients and workers. For that reason, it is vital that you name the exact state, quality and shape of the desired final product, and expect not less and no more than exactly that done. When unsure, agree to do less rather than more - the item can always return to you for additional features, but if the client has to pay for more than they asked, just because you over-processed the job, they will not be happy, while you will never get the invested time back.

This form of waste also applies to using equipment more sophisticated (so more expensive) than necessary to deliver a job. Similarly, it refers to putting overqualified personnel on simple jobs. From an Agile/Lean standpoint, agreeing to do less will achieve more as the end result.

Step 7: Defects

Defects in production are quite a standard form of waste. Not only do they demand a repeat in processing. When undetected in time, they will drive the customer satisfaction down and may cause a recall & refund wave. The crucial thing to note is ensuring that errors and defects are spotted as early in the process as possible. The later you notice them, the more time and money they will take to fix. The product’s interconnectivity with other elements is likely to grow the farther it gets into the process, increasing the number of parts you’ll need to pause, revert or change. Designing tests that check for quality at every step would be the best way to go; consider error-proofing the process.

More waste?

With Lean management maturing for a couple of decades since its introduction by TPS, the community started to list an additional form of waste: the underutilization of human skills. Lean and Kaban underline the need to pay attention to how the team’s skills are used and whether their knowledge exchanges with the managers. The workers form your company and their insights about the process should be noted and used. It’s not uncommon for company managers striving to work in a Lean way, to allow workers to make changes as and when needed - to plant Kaizen roots from the very bottom of the company up.

Examples of the eighth form of waste are underused workers’ skills, lack of vertical communication, not including the team’s perspective in process design and change, or the lack of adequate team training.

As you may have realized, the seven - or eight - types of muda are interconnected. “Over-processing” impacts “waiting”, “overproduction” relates to “inventory”, and so on. It is also absolutely possible to define many more kinds of muda in a process! Depending on your process’s character and on how deeply you want to split the analysis, it may also pay to consider types of waste such as: underused floor space, the time needed to change tools, potentially unsafe processes, wasted opportunities or planned production breaks.

What do I do now that I’ve recognized muda in my process?

Identifying the waste in your process is probably half the job to a better flowing production. For as long as you’ll apply the same systematic approach to removing it, you’re on the way to making the company more efficient.

With waste matters that are not as easy to define as, e.g., “our waiting queues are too long”, use the Kaizen approach to finding the source of a problem. With it, you will define what aspect of the process you want to analyze in this process iteration and decide how you’ll measure the effects. Then, you’ll run the production, draw conclusions and design improvement strategies, which will later need to become the standard for this process stage. Sometimes, a few runs will be necessary before you know the cause of the issue.

Example You’ve identified that your website development features are over-processed: the client asked for a feedback form to show up on their website, but what they got was extra website, under a separate URL, asking all of a user’s personal details before letting them make a comment, and in result no-one is using it, the customer lacks a way for their customers to send them feedback. For this waste, you proceed with the Kaizen event:

- Define the scope: addressing client requests in a way that responds to their exact needs;

- Choose the method of measurement: a 3-point satisfaction score: 0, 0.5, 1;

- Run the process: take the customer request and note their exact needs in action points;

- Deploy the code and review it, first with the customer - asking them to score their satisfaction from 0 to 1. Then, analyze it with the team, asking if they understood the requirements and whether they have any ideas on simplifying the communication;

- Set a standard for how the team should take customer requests, what phrasing and formatting to use (e.g., checklists, flowcharts) and how to execute them.

Generally speaking, the way in which you’ll address an identified waste will depend on its type. To better navigate your waste-solution paths, use the guide below:

| Area of waste | Solutions |

|---|---|

| Transportation | – physically localizing all connected process elements; – taking every opportunity to simplify parts arrival to their destination; – minimizing the documentation trail and using online tracking when possible. |

| Inventory | – minimizing the waste of overproduction; – analyzing and prognosing the demand when possible; – streamlining communication with suppliers to allow short term, flexible deliveries. |

| Motion | – standardizing what needs and does not need doing at each process step; – minimizing the expected communication at process steps - drawing schemas of advised problem-solving; – ensuring regular workstation servicing and workers training for any changing equipment. |

| Waiting | – allowing for process transparency for all team members; – using visual process boards showing current production status; – working on cross-qualification of team members, letting them switch workstations as and when the demand changes. |

| Overproduction | – using a Just-In-Time production scheme; – adopting the pull-based system such as Kanban to pace manufacturing; – close collaboration with clients to level the output with demand (Heijunka). |

| Overprocessing | – value-stream mapping, to show which work elements are valuable to the client; – perfecting communication with clients; – using standard requirements sheets with checklists. |

| Defects | – standardizing each process step together with QA; – error-proofing each production step; – applying DMAIC to avoid repeating errors. |

Remember not to isolate muda as the one and only non-value-adding problem crippling your process - make sure to tackle muri and mura as well. The good news is that - in many cases - applying just one solution (e.g., Heijunka or JIT) will help you address a few of the many kinds of wastes at once!